Cities around the world are racing to become smarter. Sensors manage traffic, apps connect citizens to public services, and data promises to make urban life cleaner and more efficient. At the center of this transformation is smart cities technology, often presented as a universal upgrade that benefits everyone. But beneath the excitement lies an uncomfortable question. What happens when access to these digital systems is uneven?

As cities become more connected, they may also become more divided. This article explores how well intentioned innovation could unintentionally deepen social and economic gaps, and what can be done to prevent a future where opportunity depends on digital access rather than shared citizenship.

The Promise of smart cities technology

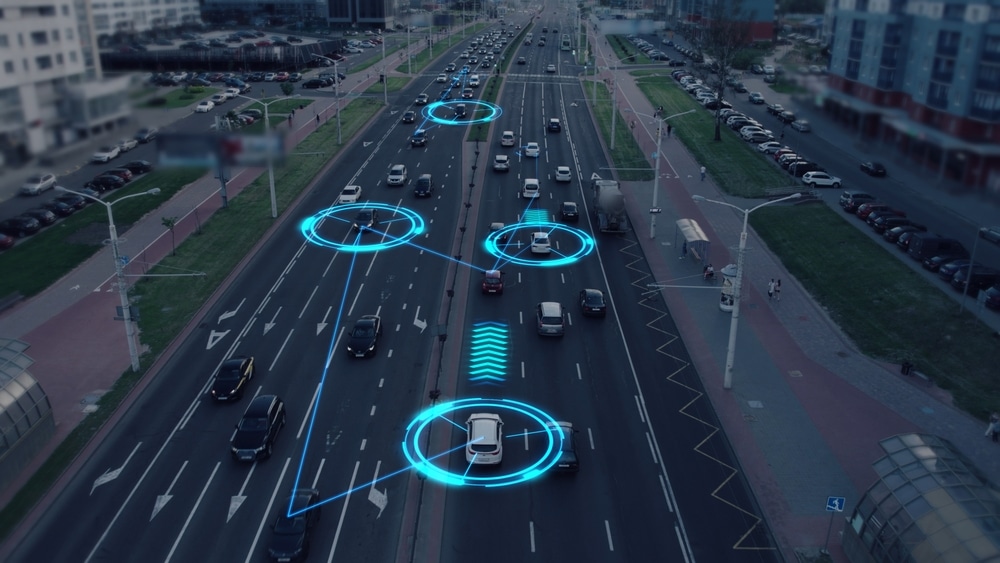

The idea behind smart cities technology is simple and appealing. By embedding digital tools into infrastructure, cities can optimize how resources are used. Traffic lights adjust in real time, energy grids reduce waste, and emergency services respond faster. In theory, this creates safer streets, cleaner air, and more responsive government.

Supporters argue that these systems improve quality of life for everyone. When buses run on time and utilities cost less, the entire city benefits. Data driven decision making can also reveal problems that were previously invisible, such as neighborhoods lacking services or areas with higher pollution levels. Used carefully, these insights can help leaders allocate resources more fairly.

However, these benefits assume that all residents can interact with and benefit from digital systems equally. In reality, access to smart cities technology often depends on owning devices, having reliable internet, and possessing the skills to navigate digital platforms. Without those basics, the promise of smarter living can quickly turn into exclusion.

Who Benefits First in Connected Urban Spaces

When new urban technologies roll out, they rarely reach everyone at the same time. Affluent neighborhoods often receive upgrades first because they already have strong infrastructure and political influence. High speed internet, smart parking systems, and app based public services appear where residents are already digitally connected.

This pattern means that smart cities technology can initially amplify existing advantages. Residents who are already comfortable with digital tools find it easier to adapt and take full advantage of new services. They save time, reduce costs, and gain access to better information about their city.

Meanwhile, lower income communities may struggle to keep up. If public services shift primarily to digital platforms, those without smartphones or stable internet access face new barriers. What was meant to improve efficiency can unintentionally make daily tasks harder for people who are already marginalized.

Access to Devices and Infrastructure

One of the most obvious risks of a digital class divide is unequal access to hardware and connectivity. Many smart city services assume constant internet access and modern devices. Parking apps, digital permits, and online consultations all rely on tools that not everyone owns.

In cities where smart cities technology becomes the default, lacking these tools can feel like being locked out of public life. Residents may miss important announcements, struggle to use transportation systems, or fail to access benefits they qualify for. The city moves faster, but only for those who can keep pace digitally.

Infrastructure gaps also play a role. Some neighborhoods still suffer from slow internet speeds or unreliable connections. Without targeted investment, these areas fall further behind as cities digitize more services. The divide is not just about income, but about geography and long standing infrastructure neglect.

Data Literacy and the New Urban Skill Gap

Beyond devices and connectivity lies another challenge: digital literacy. Understanding how to use apps, interpret data, and protect personal information is becoming essential for urban living. Smart cities technology often assumes a level of comfort with digital interfaces that many people do not have.

Older residents, recent immigrants, and those with limited education may find new systems confusing or intimidating. If booking a medical appointment or reporting a problem requires navigating complex digital platforms, these groups may disengage entirely. This creates a silent exclusion where services technically exist but remain inaccessible.

Over time, this skill gap can translate into real economic disadvantages. People who cannot engage with digital city systems may miss job opportunities, educational resources, or community programs. The city becomes smarter, but its residents are not equally empowered to participate.

When Efficiency Replaces Inclusion

A key selling point of smart cities technology is efficiency. Automated systems reduce costs and speed up processes. But efficiency does not always align with inclusion. When human support is replaced by algorithms and chatbots, people with unique needs can be left behind.

Consider a city that moves most customer service functions online. For digitally fluent users, this is convenient. For others, it removes the personal assistance they rely on. If there is no alternative channel, efficiency becomes a barrier rather than a benefit.

There is also the risk of biased data. Smart systems rely on historical information, which may reflect existing inequalities. If not carefully designed, algorithms can reinforce patterns that disadvantage certain communities, making the digital divide even harder to close.

Global Examples and Early Warning Signs

Around the world, cities are already encountering these challenges. In some highly connected urban centers, residents have reported feeling excluded from services that moved online too quickly. Smart cities technology has improved metrics on paper, while everyday experiences tell a more complicated story.

In developing regions, the gap can be even more pronounced. Ambitious smart city projects sometimes focus on high tech districts aimed at investors, while surrounding communities see little improvement. This creates a visible contrast between digital elites and everyone else living in the same city.

These examples serve as early warnings. They show that technology alone cannot solve social problems and may even worsen them if equity is not a core design principle from the start.

Can Policy Prevent a Digital Class Divide

The good news is that digital divides are not inevitable. With thoughtful policy, cities can ensure that smart cities technology serves as a bridge rather than a barrier. This starts with investing in universal access to affordable internet and devices.

Education is equally important. Cities can offer training programs that help residents build digital skills, from basic app use to understanding how data is collected and used. Libraries, community centers, and schools can play a central role in this effort.

Finally, inclusive design matters. Policymakers and developers should involve diverse communities in planning and testing new systems. By listening to those most at risk of exclusion, cities can create solutions that work for everyone, not just the digitally privileged.

As urban areas continue to evolve, the choices made today will shape how fair and inclusive cities become tomorrow. Smart cities technology has enormous potential to improve daily life, reduce environmental impact, and strengthen public services. But without careful planning, it can also deepen existing inequalities and create new forms of exclusion. The challenge is not whether cities should become smarter, but how they do so. By prioritizing access, education, and inclusive design, leaders can ensure that smart cities technology lifts entire communities rather than dividing them into digital classes defined by who can connect and who cannot.

Do you want to learn more future tech? Than you will find the category page here